Fans have always been divided about whether politics should be allowed in football. Emotions can run high and get the better of us all in an ordinary match—but when the game is mixed with something as toxic as politics, it can lead to riots.

These breakdowns in civility might be justified in the minds of those who bring violence to football, but to most of us, they might seem to be for no reason other than just to watch the world burn. Football Tribe examines five politically-charged matches that descended into chaos.

#5. 1986 China v Hong Kong

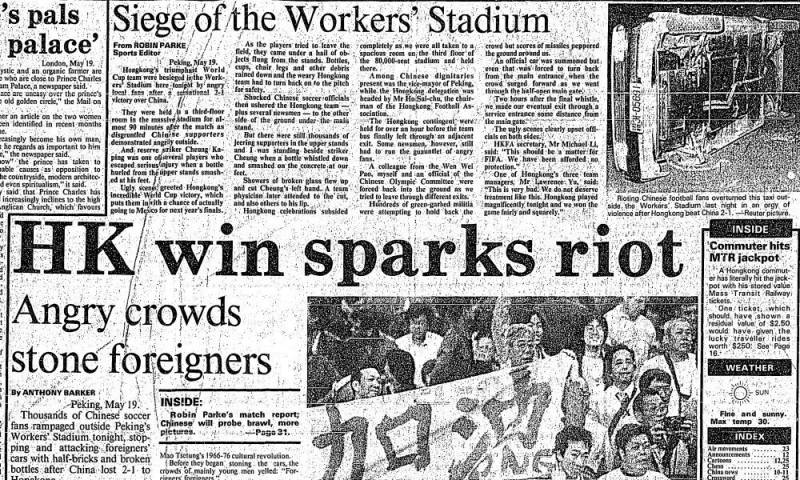

Recent events in Hong Kong have given ordinary people in China a rare opportunity to paint themselves as civilised while casting their wayward colonial cousins as domestic terrorists, but there was once a time when perceptions were the other way around. Chinese football fans found themselves capable of hooliganism for the first time on 19th May 1985, in an event now popularly referred to as the “5.19” incident (五一九事件).

The Match

China and Hong Kong were the last two teams in their group hoping to qualify for the 1986 FIFA World Cup. China was beginning to get a taste for displays of national strength and Hong Kong was still being administered as a British territory in 1985. The Sino-British Joint Declaration that would see Hong Kong returned to the fold was signed six months prior and was due to be ratified in the weeks following the match.

Hong Kong held China to a goalless draw during the first leg of the qualifying matchup at home, but they were behind in points as the Chinese team had just come out on top of one-sided matchups against Brunei and Macau. Consequently, Hong Kong had to win the second leg in Peking to qualify for the World Cup, while all the Chinese team had to do was come out of the match with a draw—which likely made their eventual 2-1 defeat to Hong Kong all the more painful.

The match at the Workers’ Stadium in Peking began going Hong Kong’s way with a spectacular 30-yard freekick by Cheung “Little Ghost” Chi Tak (張志德) in the 19th minute, and China breathed a collective sigh of relief when Peking native Li Hui (李辉) scored a goal in minute 31 and revived China’s hopes for qualification. The outcome of the match looked to be in China’s favour until the 60th minute, when Ku Kam Fai (顧錦輝) scored Hong Kong’s winning goal after a scramble for a rebound in China’s goal area.

The Aftermath

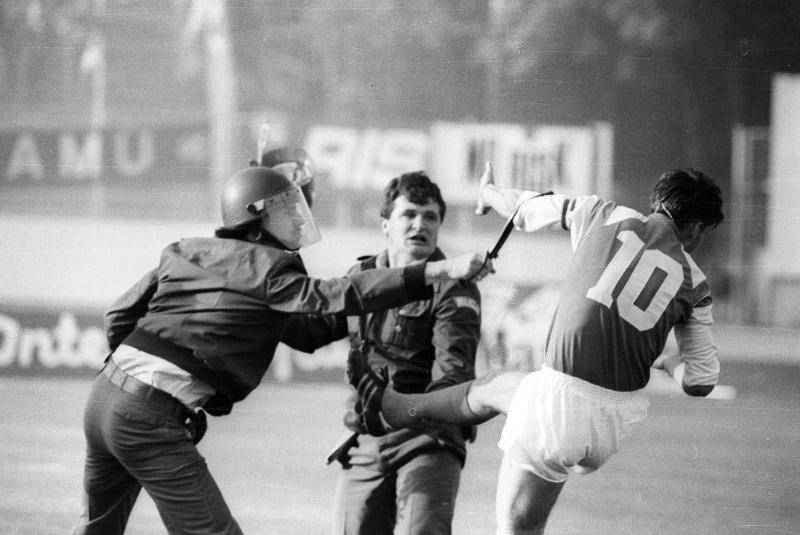

The home fans did not take kindly to this slight to their national pride. After littering the pitch with debris and attempting to block the exit of the Hong Kong team, thousands of Chinese began rioting with xenophobic fervour both in and out of the stadium; journalists were attacked and around 130 vehicles (including the Chinese team bus) were overturned or set ablaze.

The end of the saga culminated in the arrest of some 120 people, in addition to the (likely forced) retirement of the Chinese national team’s manager, Zeng Xuelin, and the chairman of the Chinese Football Association, Li Fenglou. The upset was a humiliation, and the subsequent purges were so damaging, that the Chinese national team would not successfully qualify for the World Cup again until 2002.

#4. 1990 Dinamo Zagreb v Red Star Belgrade

The details and nuances of the events that turned Yugoslavia into a conflict zone at the start of the new millennium could fill volumes and sustain whole academic careers. According to local legend, the match between these two teams, historically placed at the top of the Yugoslav football league, was where the first fires of war began.

The Match

All you really need to know is that this was a multi-ethnic nation, forged in the strife of multiple wars and held together by a cult of personality. The conflicts that resulted in the fracturing of the former republic of Yugoslavia, and one of the bloodiest conflicts at the end of the twentieth century, is said to have followed the death of the apparently benevolent dictator, Josip Broz Tito.

To oversimplify an undeniably complicated situation, after the death of Tito in 1980, a collective presidency struggled against a failing economy, rising unemployment, and growing separatist sentiment.

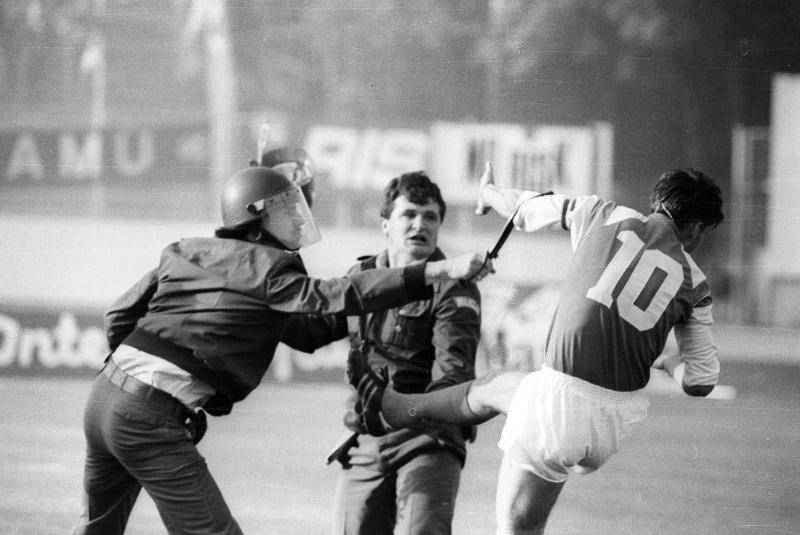

It was against this dismal backdrop, on 13th May 1990, that the match between the cities of Zagreb and Belgrade, traditionally Croatian and Serbian cities, was held. A Croatian independence had just become apparent a few weeks before, and the Croatian separatist supporters of Dinamo were on home ground in the Stadion Maksimir, hosting over 2,000 nationalist Serbian fans of Red Star who came from Belgrade by train.

The tension both in and out of the stadium erupted into a full-scale riot even before the match got underway. Stones were thrown, prompting a Serbian counterattack mounted with torn hoardings, seats, and knives. From decks to pitch, the day devolved into an all-out melee between fans, players, and police.

The Aftermath

Ultras on both sides went at each other. Dozens of fans were wounded in the chaos, and allegations of intentions to incite ethnic violence on broadcast television widened a rift of distrust that would last for at least another generation.

Some of the hooligans who were at Maksimir that day in 1990 went on to partake in a decade of armed conflict, forced migrations, and various other unspeakable crimes against humanity that left hundreds of thousands killed and millions displaced. Zeljko “Arkan” Raznjatovic, a leader of Red Star’s ultras, the Delije, went on to form a notorious paramilitary unit known as the Serb Volunteer Guard.

The Croatians and Serbians met again on the pitch a year later in 1991, this time in a match between another pair of long-time rivals, Hadjuk Split and Partizan. And while the match at least got underway this time, there was far less room for subtlety once the violence started.

#3. 2009 NK Široki Brijeg v FK Sarajevo

A single match in a new nation’s fledgling league, formed during another notorious chapter of the War in the Balkans, the Bosnian War, illustrates the depth and complexity of ethnic tensions in the region, this time between Croats and Bosniaks.

The Match

After Yugoslavia fell apart, taking the 70-year old First League with it in 1992, new lines were drawn and Bosnia was formed. As Croatia and Serbia fought each other, and sought to carve large chunks of Bosnia for the benefit of their own people, so too did the Bosniaks fight against the Croats and Serbs who lived within the borders of their new nation.

Around 500 mostly Bosniak supporters, and about half as many ultras, travelled by bus from the city of Sarajevo to the town of Široki Brijeg, where a match was being hosted. The 2009–10 season of the Bosnia and Herzegovina Premier League had just begun and another contentious local match had authorities tied up in the city of Mostar, about 20 kilometres east of Široki Brijeg.

Along the two and a half hour journey from Sarajevo, the away fans allegedly endured a wide range of mistreatment including apparent police neglect and open hostility in the form of being shot at with automatic rifles. The gauntlet to the match, and the eventual loss of the match by Sarajevo, stirred fans on both sides to violence.

The Aftermath

Mistrust of authorities deepened and the rift between the ethnic groups living in the region widened when a Sarajevo supporter, Vedran Puljić, was shot with a police pistol, and the Croat suspected of pulling the trigger, Oliver Knezović, escaped incarceration shortly after.

Around 30 people were wounded by the end of the chaos, and both sides blamed the other for inciting a riot. Croatian fans and townsfolk took to protesting in the streets to denounce the violence, while back in Sarajevo, the numbers of protestors in Široki Brijeg were matched by Bosniak fans from different clubs participating in city-wide displays of solidarity.

Široki Brijeg went on to take the second-highest position in the Premijer Liga tables that season, making it into the first qualifying round of the 2010–11 UEFA Europa League, while the Fudbalski klub Sarajevo had to wait for the following season of the Bosnia and Herzegovina Premier League to take that same position in the league table.

#2. 1909 Rangers v Celtic

The great-grandfather of football rivalries is undoubtedly that of the Old Firm, the Celtic and Ranger football clubs of Glasgow, Scotland. Any meeting between these two rivals, even in the present day, is all but guaranteed to be a spirited match. One in particular, in 1909, could be the event responsible for sustaining the rivalry for many more generations.

There are multiple reasons for the rivalry between the two most popular Scottish football clubs: history, politics, religion, and everything else in between. But we will be glossing over all the fine details of this 130-year-old saga to focus on one particularly intriguing match that occurred over a century ago in 1909.

The Match

The “Old Firm” rivalry would probably have just been called the “Firm” rivalry in 1909. It was that long ago. The Celtic and Rangers football clubs had (only) been dividing Glaswegians for a couple of decades—so when they met at Hampden Park, as they often do, the stadium was packed with a generation of fans raised on this conflict.

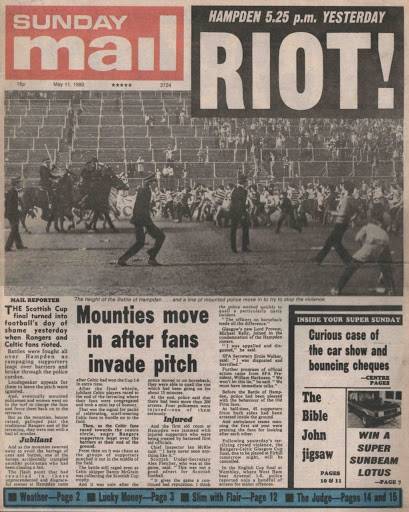

The two teams had met for the Scottish Cup final on 10th April, and with the match having ended in a draw (2-2), a replay match was played a week later on 17th April. The replay also ended in a draw, with one goal each having been scored by the two teams’ Jimmies (Celtic’s Jimmy Quinn and Rangers’ Jimmy Gordon) leaving fans and players of both teams standing in the stadium awaiting an announcement of extra time.

Expectations of extra time were not satisfied, and a second replay, when extra time would be allowed, was scheduled for the following week. But with fans already circulating conspiracies of result manipulation to maximise income, and an inebriated fan having been assaulted by police, a mass pitch invasion ensued.

The rivalry was temporarily forgotten as fans from both sides united to make their feelings known. The pitch was torn apart by 60,000 fans over the course of a few hours. Wooden barriers were used to set fires, projectiles were thrown, and police were attacked, resulting in hundreds being injured.

The Aftermath

When the riot eventually left Hampden Park and moved northwards into the centre of Glasgow, it left damages that required reparations amounting to £800 (just under £100,000 in 2020 money) and had Glaswegians proposing the substitution of police at matches with soldiers and fixed bayonets.

The violence was of such a degree that the Celtic and Rangers football clubs issued a joint statement requesting that the Scottish Football Association scrub the second replay. As a result, the Scottish Cup, the world’s oldest national football trophy, was withheld for the first and only time in its history.

The rivalry, of course, continues to this day.

#1. 2004 Al-Jihad v Al-Fotuwa

Aside from the unknownable and ancient quarrels that divide Kurds and Arabs around the world, it can be said that the beginning of Syria’s woes in the 21st century, as well as the flight of the Kurds into northern Iraq, can be traced to one local football match in Syria on 12th March, 2004.

The Match

For various reasons that are about as old as time, the Kurds are a distinct culture and ethnic group that is often persecuted throughout much of the Arab world. Following some arbitrary redrawing of borders in the early 20th century, the Kurds wound up in a largely borderless region that includes parts of northern Iraq and Syria, where the city of Qamishli, considered a hub for Kurds in the region, is located.

The local Kurdish football club in Qamishli, Al-Jihad SC, was set to play against Al-Fotuwa SC, a visiting club from Deir ez-Zor, another Syrian city located around 200km to the south. The day of the match had busloads of Arab fans flocking to Qamishli and engaging in trash-talk with the Kurds, which led to both sides (allegedly) partaking in assaults, looting, and a full-scale riot that lasted several days.

The Aftermath

In the heavy-handed attempts by the Syrian military to quell the unrest, dozens died, hundreds were wounded, and thousands were arrested. The violence was of such a degree that the details of the match, such as whether play officially began or who won, have apparently been lost to the fog of war.

In the decade and a half following the riots in Qamishli, thousands of Kurds fled to northern Iraq and paramilitary groups rose to fight the Syrian army. The unrest that followed this match in Qamishli is still observed as the beginning of the Kurdish uprising in Syria.

Were you in Qamishli on 12th March 2004? Are you privy to the details of the match? Let us know how it turned out.

Stay tuned for our roundup of the times when humanity won out on the pitch.